Carl Green

Book Review

This review originally appeared in St. Louis/Southern Illinois Labor Tribune on May 21, 2018

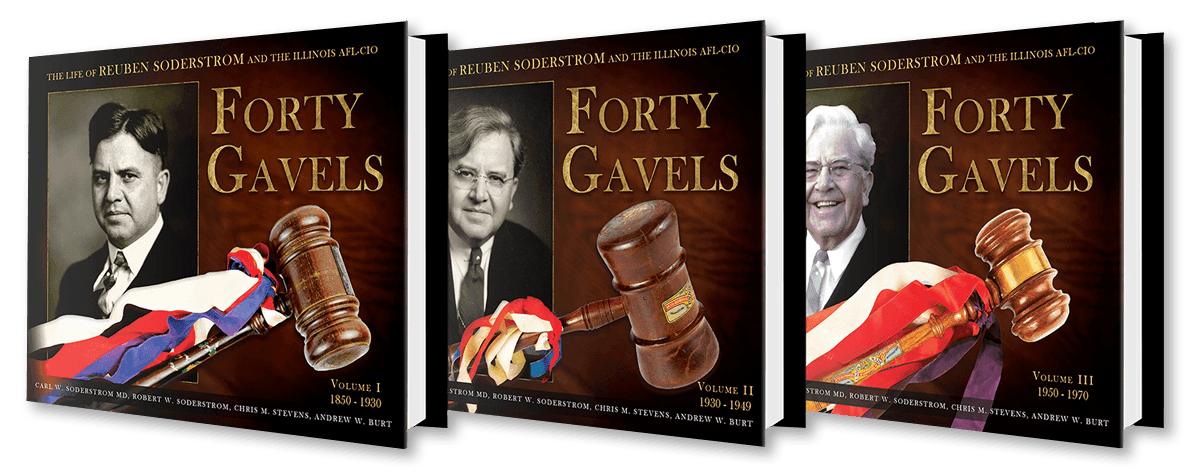

For forty years, 1930 to 1970, Reuben G. Soderstrom stood at the top of the Labor Movement in Illinois as president of the Illinois State Federation of Labor and its successor, the Illinois AFL-CIO.

His tenure ranged from the Great Depression through World War II and deep into the era of the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam. Labor’s importance grew enormously during that time, and it was Soderstrom who kept things moving forward in the Prairie State.

AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka says Soderstrom was a “progressive beacon” and Illinois’ “guiding light” as that random, scattered movement evolved into a powerful, united force for working people.

Yet most people these days have never heard of Soderstrom, much less know of his accomplishments for Labor and in the Illinois House of Representatives. His tenure with the Illinois AFL-CIO ended shortly before his death in 1970 at age 82.

Soderstrom’s story is also the story of the rise of Labor in Illinois in those crucial decades. And now it has been told, in one of the biggest and most thorough biographies ever written.

HOW IT HAPPENED

Chris Stevens, a veteran writer for The Labor Paper, a Peoria-based, twice-monthly newspaper for central Illinois, said the process began in 2008 when the Illinois AFL-CIO dedicated its headquarters in Springfield, 50 years after it was formed by merger.

Labor Paper Editor Sharon Williams noticed then that the president in 1958 was named Soderstrom, just like a dermatologist in Peoria, Carl Soderstrom.

Williams contacted the doctor and learned he was Reuben Soderstrom’s grandson – and very proud of it, so much so that he had always wanted to write a biography of his grandfather.

Williams put Carl Soderstrom together with Stevens, and that laid the foundation that became the project that became the book.

Stevens soon found out that Dr. Soderstrom was ready to create a really big book.

“Doc always wanted to tell his grandfather’s remarkable story. In addition to his vast memories, he had a handful of photos and a couple of newspaper articles about Reuben,” Stevens told the Labor Tribune. “He also had the gavels from Reuben’s years as president. He hired me, and we started doing research.

“We went through the convention minutes of the 40 years he was president. We found a huge number of newspaper articles, which of course then lead us to more information.”

Stevens made several visits to the Richard J. Daley Library at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and he and co-author Andrew Burt spent two weeks at University of Maryland’s Hornbake Library, official repository of AFL-CIO records.

“Doc is a scientist by nature, training and education, so he insisted upon accurate information and citations,” Stevens noted.

A BOY’S HARD LIFE

The story of Reuben Soderstrom’s childhood, as related in the first volume, is a microcosm of American history, reflecting a wholly different way of life from what we know now. He was born in 1888 in rural Waverly, Minn., the second of six children, to immigrant parents John and Anna Soderstrom.

The family’s story could be a book itself as they try to live the American dream only to run into crop failures, poverty and infant death. John, born a Swede, pursues farming and preaching careers and works as a laborer as well. But it’s not enough.

At age nine, Reuben is sent to work and stay at a blacksmith shop to help pay off family debts. Three years later, in 1901, he is sent to Streator, IL, a coal mining town southwest of Chicago, to find work and send his earnings home to support the family, while living with an aunt, the wife of a coal miner.

After hauling water bottles for work crews for $3 a week, the boy moves to a bottle factory, where he joins in his first strike in 1903 but gets nothing to show for it.

Reuben’s sister Olga later wrote a detailed description of these early years and concluded they explain well the impulses that pushed her brother into becoming a Labor leader.

“He knew poverty firsthand,” she wrote. “He experienced child labor. He knew the loneliness of separation from his family at such an early age. These were his formative years, and they were not happy years.”

SELF-EDUCATED AND INNOVATIVE

The young man discovers the library, studies the words of Abraham Lincoln and Alexander Hamilton, and uses his new language skills to build a career as a union linotype operator. He remains a member of the International Typographers Union for 60 years.

His union work leads the young man to win a seat in the Illinois House in 1918, lose it in 1920 and win it back in 1922, and he pushes through important Labor legislation including the 1925 Injunction Limitation Act, which gave unions the right to peacefully assemble and go on strike.

Soderstrom develops the idea of “agreed bills,” in which adversaries agree on what they will accept in advance, allowing the legislation to become law smoothly. He eventually serves 18 years in the Legislature.

LANDMARK PENSION BILL, PATRIOTISM, WORKER PROTECTIONS

As Volume 2 takes over the story, the now-veteran legislator gets a landmark pension bill passed and is elected president of the Illinois State Federation of Labor in 1930. During World War II, Soderstrom takes the patriotic approach, working to keep his member unions from striking against wartime production.

In the 1950s, he helps bring about the national merger of the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Occupations to form the mighty AFL-CIO, including the Illinois AFL-CIO, where he continues as president. He battles in the Legislature to strengthen protections for Illinois workers.

In Volume 3, readers see an older Soderstrom coping with the fast-changing world of the 1960s. He works with both presidents, Kennedy and Johnson, as they sometimes support and sometimes oppose Labor interests, and he becomes a friend of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in championing the Civil Rights Movement.

But he also finds difficulty, as a lifelong Republican who supported FDR, in building the kind of consensus that had been his way of getting things done.

There’s much more to tell, but that’s why they wrote the book.

CELEBRATION OF LABOR MOVEMENT, WORKING CLASS STRUGGLES

Carl Soderstrom, the co-author and publisher of the book, says in his preface that the book is rare in the way it celebrates a working class man’s difficult life instead of the usual stories of thriving economies and titans of industry.

“The book you are holding is important because it is an unapologetic celebration of the Labor Movement, its colorful and committed laboring men and women, and a singular man, my grandfather, Reuben George Soderstrom, who steadfastly and charismatically churned through the decades as its fearless leader. “For me, this project has been a study of a great man doing great things.”

This region’s prominent Labor historian, Mike Matejka of the Great Plains Laborers District Council and vice president of the Illinois Labor History Society, managed to sum up the three volumes in two succinct sentences:

“A child of rural immigrants who started work early, Reuben Soderstrom quickly grasped that his situation was not unique but shared by millions. With a strong moral foundation from his religious family, he became a life-long workers’ champion – a visionary with the patience to struggle relentlessly to bring change.”